True to name parrying daggers were primarily an off-hand weapon used in combination with a rapier or other sword in the dominant hand. Unlike other daggers of the day that were usually used as offensive weapons that could be quickly drawn with the main hand (often in an overhand "ice-pick" grip as in the example of rondel daggers here), parrying daggers were primarily a defensive weapon. Combat with the rapier and parrying dagger is a complex system that is detailed in manuals such as Nicoletto Giganti's 1606 "Scola, overo teatro", and Ridolfo Capo Ferro's 1610 Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma. It is an elegant fighting style that requires significant skill and grace and would have been common in the hands of renaissance gallants from Shakespeare's London to the streets of fair Verona.

In use

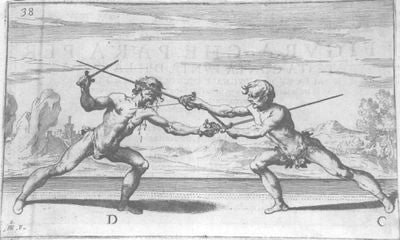

In the below image from Capo Ferro you can observe the two fighters at guard with rapiers extended and daggers held back. The fighters lean away from each other to protect their vital organs and faces from a quick lunge and give them time to counter an attack.

When the fighters engage, the dagger is often used to move the opponents sword blade off-line, opening the way for an attack with ones own sword. This means that the parrying dagger takes some of the defensive activities of the sword, freeing the sword to make simultaneous attacks. Of course, this works best when fighting an opponent whose weapon is primarily used in the thrust, not because a heavier sword will necessarily cut through a parry with a dagger, but because thrusts present the weak of the blade in a manner that allows it to be easily offset.

As you can see from these illustrations, the deflecting action may move the opponents sword in any direction that is advantageous, inside, outside, above or below. The long curved quillions on some parrying daggers seem useful in preventing the opponents sword from slipping around the hilt, making disengaging actions larger, and therefore slower. The two plates below are from Giganti's 1606 text.

One of the common features on parrying daggers is a side ring or sail on the guard. This is for protection of the hand. When the dagger intercepts the opponent's blade it is often at such an angle that the back of the hand is exposed to possible injury. The ring helps to deflect the opponents blade from piercing the back of the hand and wrist, an injury that could prove quite significant if it severed tendons or the arteries in the wrist. The arms of the hilts are often symmetrical, so they may be used effectively in either hand. This feature is more likely due to the difficulty of carrying a dagger with rings on both sides of the hilt than for Princess Bride-style ambidexterity.

When people who are unaccustomed to these weapons pick them up for the first time (especially at Renaissance Fairs), they tend to assume that the ring on the hilt is for putting ones fingers or thumb through. This is a very bad idea. Not only does it expose your thumb to the possibility of being cut, but when the fight turns to grappling it is an excellent way to get your thumb broken clean off.

Good! Bad!

Arms & Armor Parrying Daggers

Below we have included a selection of parrying daggers that we make. In cases where the dagger is part of a matching suite we have also included its rapier. Enjoy!

Arms and Armor Milanese Parrying Dagger and matching Rapier

Arms and Armor German Parrying Dagger

Further research

Good article on Parrying Daggers by Leonid Tarassuk click here for pdf download

Nathan Clough, Ph.D. is Vice President of Arms and Armor and a member of the governing board of The Oakeshott Institute. He is a historical martial artist and a former university professor of cultural geography. He has given presentations on historical arms at events including Longpoint and Combatcon, and presented scholarly papers at, among others, The International Congress on Medieval Studies.

Craig Johnson is the Production Manager of Arms and Armor and Secretary of The Oakeshott Institute. He has taught and published on the history of arms, armor and western martial arts for over 30 years. He has lectured at several schools and Universities, WMAW, HEMAC, 4W, and ICMS at Kalamazoo. His experiences include iron smelting, jousting, theatrical combat instruction and choreography, historical research, European martial arts and crafting weapons and armor since 1985.